In a traditional business model, core business assets included property, equipment, inventory, and cash. The tangible things we understand as having value. As we transitioned from an industrial revolution to a technological one, however, there was a new asset introduced that has been harder to qualify: data.

According to The Big Data and AI Executive Survey 2020, the percentage of firms investing more than $50M in their data is up to 64.8% in 2020 (compare to just 39.7% in 2018), with a total of 98.8% of firms investing in Big Data and AI initiatives. Businesses of all sizes are racing to adopt data-driven strategies in order to not only spur innovation within their business models but upend traditional practices by prioritizing data-driven decision-making over instinct.

Concurrently, we’ve seen the rise of the data economy. According to Gartner, by 2022, 35% of large organizations will either be sellers or buyers of data via formal online data marketplaces, up from 25% in 2020. Data is becoming commoditized as more of it becomes available and its potential is explored. As it has been said many times, data is the 21st century’s most valuable resource.

The Problems with More Data

The tension at the heart of this new resource is around access, use, and governance. The exponential increase in available data has not automatically led to an increase in usage. Technological, institutional, and regulatory barriers are currently limiting the adoption of external data and also, surprisingly, the use of internal data assets.

This has created a problem for organizations that have invested in their data infrastructure. In order to access data they see as valuable (or potentially valuable – the benefits of experimentation for data-driven businesses are clear), they have to provide dedicated internal resources to find, connect to, and manage external data feeds or set up individual licensing agreements with dozens of data vendors. The first case is a misuse of time and the second a misuse of resources.

Even when an organization dedicates energy, time, money, and talent into gathering data from the public domain and data providers, the problems of data governance surface. “Now that I have access to data, what am I allowed to do with it?” This point is especially contentious, since data governance compliance is a moving target.

In recent years, the GDPR and CCPA have provided robust frameworks that support and limit the use of data; but for many organizations, these regulations are hard to interpret and harder to implement. Given that many data warehouses look less like a library and more like a swamp, the sudden need to understand the shape, structure, and composition of their data is a daunting task.

Given these difficulties, organizations at every level – including governments of every size, NGOs, and large enterprises – are exploring ways to use more data, integrate with organizations releasing data, and build products and services that scale with usage.

The Answer May Lie in Data Trusts

There is no universally agreed-upon definition of what a data trust is. The Open Data Institute (ODI) defines them as structures “that provide independent third-party stewardship of data,” with informed consent from the data subjects. Data trusts also guarantee that the people who have data, use it, and are affected by its use have a mechanism to ensure that it is shared equitably. A successful data trust is a set of principles that facilitate the interaction between citizens, governments, and third-parties, promoting open and democratic access to data.

The rules which guide a data trust may not be concrete, but there are several key infrastructure components that are crucial when designing one:

- The ability to access new data,

- Custom, fully controlled provisioning of data assets by data stewards,

- The development of role-based methodology for governing data use,

- Connecting data through an API-based vascular system to interface with third party tools.

What are the Benefits of a Data Trust

A data trust lays the foundation for data innovation while enforcing strong governance principles, allowing for secure and scalable data sharing. It provides increased control for the data provider over their data assets by letting them control the flow of their data: who gets it, what they get, and where it resides.

Data trusts also allow for rapid consent-based data sharing at scale between the data user and provider. Without a data trust, data providers have limited visibility into how their data asset is being managed, integrated, or protected. As it currently stands, the majority of data agreements are ad hoc, and data is shared through outdated (and non-secured) means like USB drives, FTPs, and emails. If organizations don’t modernize their data flow-through, this process will raise serious security and scalability concerns long term.

The Case for Centralized Access

To put this problem into perspective, we can look at the recent pandemic. In early March, an abundance of epidemiological data was released from a variety of sources, from Johns Hopkins University and the World Health Organization (WHO) to local health units across the world. The speed at which the crisis unfolded made it impossible to drive a standard across all these data providers in real time. The value of this data for researchers trying to understand how the pandemic was evolving was buried under the practical consideration of manually connecting to and cleansing data from dozens of places at once. It was, in effect, a microcosm of the problems that have been inherent in accessing public data for the past decade: information was available, but not very accessible.

ThinkData became a founding member of the Roche Data Science Coalition (RDSC), a group of public and private organizations working with the global community to develop solutions around the COVID-19 pandemic. Committed to sharing knowledge and public data, the coalition developed relationships with data providers to break down the silos between the people who have access to useful information and the people who can use it to better understand the crisis.

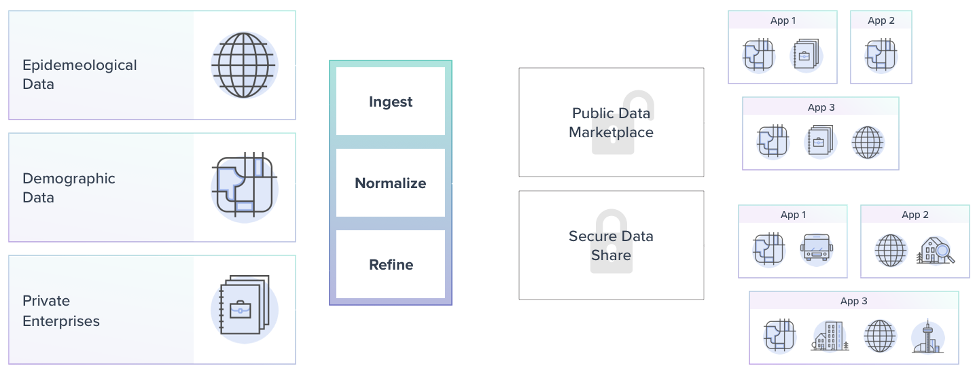

Roche and the RDSC used epidemiological and demographic data from governments, research institutions, and private enterprises to understand the underlying trends in the spread of COVID-19. As a founding member of the RDSC, ThinkData provided Namara, our end-to-end data access solution, as a central access point for publicly-available datasets gathered from around the globe.

Working with the RDSC, ThinkData established rules and governance principles about what data should be included. Since researchers were building analysis and applications on this information, it was critical to be able to consistently vouch for its provenance and quality. The data also moved fast, with individual datasets sometimes updating several times per hour. A lot of these datasets were being manually created by hospitals and NGOs, and it was critical to catch instances where some harried researcher mistakenly added an extra zero to the daily case total. By running all these sources through our Dataspec service, we were able to monitor the data as it changed over time and catch any outliers at the moment the data was ingested.

In the RDSC, ThinkData operated as the primary aggregator of the public data that was being released. As a company founded on open data, we were more than happy to supply the platform to researchers and the coalition to help drive insight.

Ultimately, though, it was limiting to have our team find and provide access to new data as it was released. What would be better, we realized, is if every hospital, researcher, and data-driven institution could tie into the platform themselves, where they could provide daily data using secure and structured APIs, redact sensitive information at will and share custom views of this data with the research community. This is the difference between a data provider and a data trust – putting access control into the hands of the data steward, and unlocking new opportunities for collaboration and innovation. We were thrilled to let our data partners know that all of this was possible with the new Enterprise Edition of Namara.

Who Benefits From a Data Trust?

As businesses continue to find ways to use, monetize, and aggregate data, they need to effectively share their data in a way that’s more secure than an email and more scalable than sending a thumb drive by courier. They also need methods to use data more efficiently. In particular, businesses that are exploring ML and AI solutions need to look to data trusts to provide these solutions at scale, because the tedious overhead of data prep required to fuel these solutions can derail projects entirely.

Data trusts are also a logical next step for any government or government institution looking to achieve greater transparency and drive innovation. After all, a data trust is primarily a vehicle for securely collecting and disseminating public, private, and proprietary information. Government data systems are complex; data trusts are a useful tool that can be used to synthesize, standardize, and audit data that is generated or used internally.

The key difference between the value that data trusts bring for businesses is to increase data use within the organization, whereas for governments it is primarily used to audit data assets and better understand internal data environments. A trust that is used by both business and government institutions is more powerful still, creating accountability at scale, driving private sector investment, and improving services and innovation for the rest of us.

A third, more niche, use case for data trusts are innovation hubs. Sitting somewhere between government and private enterprise, these entities aim to make good on the promises of a more connected society. Innovation hubs rally citizens, academics, researchers, and the private and public sectors to address critical issues facing our cities, our planet, and our future. They are a bridge between data generators and data users, gathering information, tools, talent, and processes under a common mandate – the perfect application of a data trust.

More Access, Better Data

The difference between organizations that want to be data-driven and those who are isn’t the data – it’s the way that data is handled. The legal structure of a data trust depends on the use case, but there are shared technological components of data trusts that are required to ensure increased confidence and less overhead for those involved. By adopting a sharing ecosystem that streams data through a central clearinghouse you are well on your way to building a successful data infrastructure to build your data strategy off of.