The Data Ethics Conundrum

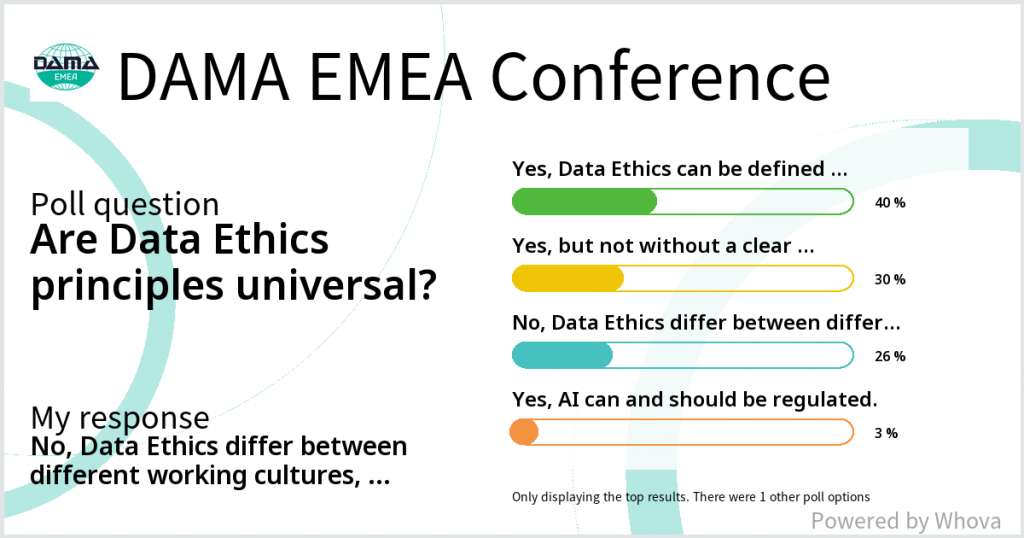

The recent DAMA EMEA conference was a valiant effort to connect the DAMA membership in the EMEA region through an innovative virtual conference format. During the conference, various polls were run. One of these polls asked, “Are Data Ethics Principles Universal?”

Before I go any further, I’ll just say that the sample size of respondents to this poll was quite small at the time of writing (n=30). However, the options for response were somewhat constrained and leading. Oh, and the survey tool had a bug which brings in responses from a different poll into the results, leading to less than reliable data quality.

So, my discussion here will be limited to the qualitative issue rather than being a direct quantitative analysis.

The First Problem

The first problem with this question is that, in common with much of the recent discourse on ethics in information management, it confuses the object of the sentence. We do not have “data ethics”.

Such a thing DOES NOT EXIST.

We have ethics. And ethical principles. And ethical practices. And we can apply those to data and to questions of data management and data governance and the application of machine learning and other things.

But there is no single master list of Ethical Principles we can look up or call like a stored procedure into our moral code. If there was, the discipline and study of philosophy (and for the purposes of this article, I include religion under the broad umbrella of the term “philosophy”) would be a long weekend self-study course with a multiple-choice exam at the end. A bit like the professional certifications that are so important in our industry.

In Ethical Data and Information Management: Concepts, Tools, and Methods, my colleague, Dr Katherine O’Keefe, and I tried to give a high-level introduction to the broad scope of the schools of ethical philosophy that people might encounter in their thinking on ethical issues in data. Here’s the thing… we had to leave a massive amount of important stuff out. I’m painfully aware that, notwithstanding, the efforts we made to give a good grounding in ethics and make links from different schools of moral philosophy to the questions that arise in data management, there was too much white and western thinking in those chapters. And even with limiting our scope to just the DWPs (dead white philosophers), we had to satisfy ourselves with establishing in broad terms what those DWPs were setting out as principle and highlight where there were overlaps and differences between the different DWP schools of thought.

To an extent, the world of ethical information management is in a similar position to the world of quality management applied to data and information or governance for data and information. We’ve screwed up the object of focus and have lost sight of the fact that what we are actually trying to do is apply principles, practices, and ways of thinking from other domains to the domain of data, making modifications along the way where we need to those practices so that they are appropriate to the challenges and opportunities we face.

Of course, we are also facing the same problem as quality management that Joseph Juran wrote about in the 1980s when discussing the quality crisis in the US. Chapter 10 of Ethical Data and Information Management looks at that in more detail so I won’t dwell on it here. Suffice it to say, it shows the importance of not putting too much faith in revolutions as they have a nasty habit of coming around again.

Even focusing on just DWPs, there is a broad scope of ethical principles that can be adopted. From the deontological structures of Immanuel Kant’s Categorical Imperatives to Rawls Social Justice Theory, to good old Consequentialism, there’s a lot to choose from. And that’s before we look at feminist ethical theory, Confucian ethical concepts in Asian philosophies, or ethical systems such as Ubuntu or the ethical constructs of indigenous cultures around the world.

So, having established that the fundamental question posed by the poll belies a misunderstanding in our industry of what ethics is as a field of study, we can now dissect the responses.

The Second Problem

The second problem is that the poll set out four options, each of which is a leading response. Bluntly… all these answers are arguably correct. They are also all wrong.

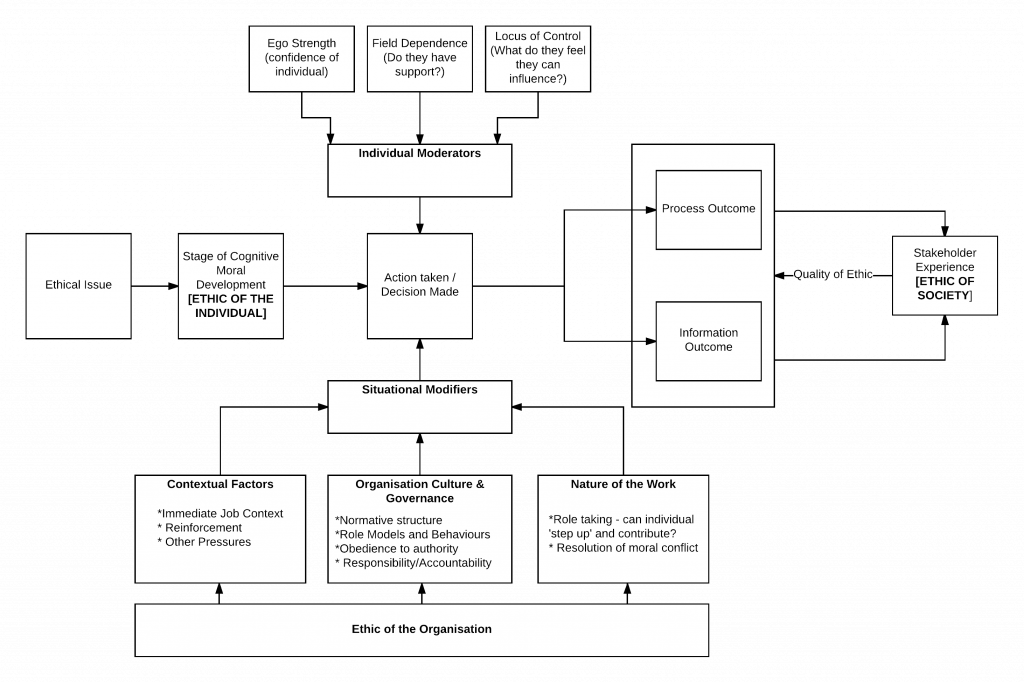

In the book, we introduce the concepts of “Ethic of Society”, “Ethic of the Organisation”, and “Ethic of the Individual”. Working with clients we also address the idea of “Ethic of the Group”, a sub-set of the organisation. I’ll discuss why this is a Schrodinger’s Cat of an answer choice now.

Within a company (the Organisation), it is possible to define ethics as part of the culture of the organisation and then apply those principles to the governance and management of data. Of course, this requires clear communication and commitment to establish those cultural norms and what are referred to as the “Situational Moderators of Ethical Behaviour”. And even then, how those cultural norms around ethics are interpreted and applied by individuals in the organisation can be subject to significant influence from the “Ethic of the Group” (e.g. a team or department or peer group), or the locus of control or influence that an individual has in the Group or in the Organisation (aka “Individual Moderators of Ethical Behaviour).

And this is before we even consider the impact of the Ethic of Society when that society is culturally non-homogenous within one geographic region or may span multiple countries and cultural ethical frameworks, but against which the question of whether the outcomes of the actions taken by the individuals in an organisation with or relating to data are ethical or not will be judged (the “Quality of Ethic” as we termed it in the book).

Source: Ethical Data & Information Management: Concepts tools & methods.

Click on image to see larger version.

The Third Problem

The third problem is that data people don’t seem to get this, even after a number of years of hand-wringing and pearl-clutching about the ethical issues in data management. It was fascinating to see so many presentations this year at DGIQ on the topic of “data ethics” (see problem 1 above). This shows that there is a concern and a wave of interest. But, as I reference in Chapter 10 of the book, this is pretty much the place the Quality movement was at in 1986 when Joseph Juran decided to light a fire under them.

Looking at the poll from the DAMA EMEA conference, the results break down as follows:

- 40% said data ethics can be defined universally across sectors, countries, and communities

- 30% said yes, but not without clear communication and commitment

- 26% said No, because data ethics differ between different working cultures, sectors, and countries

- And, if we ignore the erroneous 4th answer the survey tool pulled in, we can infer that 4% of data management professionals who expressed a preference said No, that ethics are something individual

I’m still trying to figure out if the framing of the question and the leading nature of the options presented is the signal that we have a fundamental lack of understanding of ethics and ethical issues as a structural and organisational construct among the data management profession or if the answers to the question are the signal. Maybe there is a massive population of wise sage data management professionals who looked at that poll and decided that it was grounded on flawed premises and wasn’t worth contributing to (but I doubt it).

Either way, I think we have a fundamental problem where there continues to be clear understanding of what ethical information management is and what it entails for leaders in organisations to actually address this challenge. Because it is about a heck of a lot more than Fair Information Processing Principles from the world of data privacy, and other weak-sauce ethics content that has been tacked onto data management methodologies and certifications in recent years.

The Fourth Problem

The fourth problem we have is one that is shared with the burgeoning buzzword of “Data Literacy”. In effect a bunch of quants from technology or CompSci backgrounds have decided that those Humanities disciplines that they have tended to value less than traditional STEM skills have realised that these are very important topics.

But if 70% of data management professionals who expressed a preference are of the belief that we can define universal data ethics principles we have a problem. Because it means that our data management professionals don’t understand the problem and cannot frame or express it in a form that lets us solve the equation for X.

And this brings us to the question of data literacy which is about a heck of a lot more than just competence in using tools, interrogating data sets, and producing visualisations, just as it is also not exactly about the digital media literacy skills you need for critical thinking about misinformation on the internet. And that discussion of data literacy and data competencies is a topic I’ll return to in 2022.

It is relevant here because for most data professionals there isn’t a need to develop a deep philosophical understanding of all the nuances of ethics and moral philosophy. But for others it will likely be an essential skill set in the context of their job role in the future. For most of us, it will be sufficient to understand that the Ethic of the Org is [insert cultural value here] and this is enforced through the organisational governance structures such as Data Governance and where there are conflicts with the Ethic of the Individual a forum exists where that can be aired.

But the harsh reality of ethics in information management is that the Ethic of the Organisation and the governance and reward systems are the battleground that whistle blowers fall on, with the last few years seeing some high-profile resignations and sackings and many more subtle demotions and ‘moving to the side’. This even affects staff with a mandate to oversee regulated processing such as data protection compliance.

On the evidence in front of us, the only universal data ethics principle is that “Snitches get Stitches”.

The Solution?

Even in Star Trek, the United Federation of Planets hasn’t cracked the problem of different ethical frameworks and principles across the various cultures and species in the Federation. And the last few thousand years of human thought on the topic hasn’t solved the riddle either.

Rather than seeking universality in principles, a different approach is needed that enables us to find the commonality in ethical principles while recognising and respecting the differences. This may mean we have to develop governance processes for data that can navigate the divergences while standardising processes around those areas of homogeneity in outlook and outcome.

However, as we still struggle as a profession to define the concept of “Customer” consistently, I fear we may yet struggle with this.