I was giving testimony to a Joint Committee of both Houses of the Irish Parliament on data sharing legislation earlier this week. As part of the testimony I and other witnesses were giving, a discussion of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation as principles based law addressing how organizations should handle data about people (the GDPR was not the legislation I was testifying on, but it was a relevant side-bar discussion).

I was giving testimony to a Joint Committee of both Houses of the Irish Parliament on data sharing legislation earlier this week. As part of the testimony I and other witnesses were giving, a discussion of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation as principles based law addressing how organizations should handle data about people (the GDPR was not the legislation I was testifying on, but it was a relevant side-bar discussion).

During the questions from elected representatives that followed, one of our Senators asked a pointed question drawing an analogy between one of the root causes of the collapse of the Irish Banking sector and the risks of “light touch” regulation.

They commented that the Irish banking system had moved from a prudential based system of robust checks, balances, and controls, to a “principles based” model of regulation, which was then accompanied by a shift towards “light touch” regulation. That, in turn, lead to improper lending, poor risk management, overheated the property market, and left the balance sheets of banks and other lenders exposed when the crash inevitably came.

In the context of the legislation I was giving evidence on, this was an important point. One of the criticisms I, and others, have raised of the Irish Government’s proposed Data Sharing and Governance Bill, which is proposed as an umbrella law to allow broad sharing of data between public bodies without a need to enact any further legislation, is that it puts the cart before the horse and emphasises sharing rather than governance. This was the case back in 2014 when I first reviewed the draft scheme of the Bill, and in 2015 when the draft Heads of the Bill (the outline specification for what the law will look like) were published for review – and it remains the case today. I won’t bore international readers with a detailed analysis of the issues and weaknesses with this legislation. Suffice it to say that discussing it with the Joint Committee of the Irish Parliament gave me an opportunity to:

- Define and explain what Data Governance is

- Explain why a failure to have effective Data Governance is a key root cause of failures in data interchange and data linking projects within private sector organizations

- Introduce the concepts of metadata and data definition to elected representatives (and, more importantly, have them on the record of the Irish Parliament)

- Highlight the cost of non-quality information in the average organization, and point out that failure to address Data Governance in organizations is a key root cause of the hidden information factories, scrap and rework, and general duplication of effort checking and correcting data or responding to issues when data is used for purposes it was not fit for.

I will post a full video of my testimony, and the testimony of my fellow witnesses, as soon as my media techies have stitched the two halves of the official video together.

However, the question about the weakness of principles based legislation and “light touch” regulation required me to give an answer that experienced Data Governance professionals will find familiar, and which new entrants into the field will need to learn – and FAST.

Ultimately, all governance in organizations is principles led. Regardless of the legislative driver that triggers the need for the governance models to be introduced, the operational imperatives that need us to improve the co-ordination of data-related activities, and the industry standards that may require us to implement controls in our organizations, the rubber hits the road with the correct definition of and application of principles.

Chapter 4 of Bob Seiner’s book “Non-Invasive Data Governance: The Path of Least Resistance and Greatest Success” is devoted to discussing principles for Data Governance. John Ladley’s book “Data Governance” also discusses the importance of principles in defining the vision for your Data Governance initiative. However, the type of principles I am referring to go a little deeper then that. They are the fundamental ethical principles we would like to see applied in the handling of data. These are the bedrock on which the principles discussed by Bob and John sit, and those principles are the foundations on which the governance models in organizations are built.

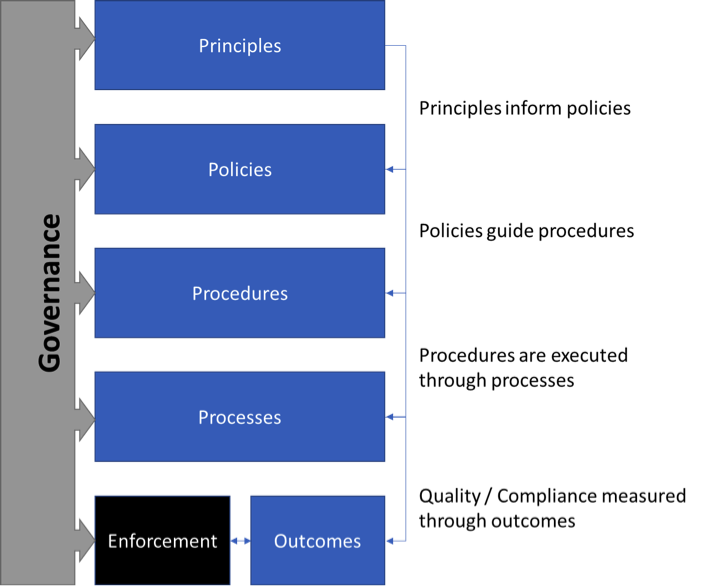

And that was the point I made to the Parliamentary Committee. I extended it a little though, as we need to learn the lessons of Governance failures in organizations. Effective Data Governance initiatives (or indeed any kind of governance) need to make a clear link from Principles to Outcomes, and if the Outcomes are not what was desired or expected, to Enforcement.

I call this the “Hierarchy of Governance”. I’ve presented it here as a top-down model, with Principles at the top, but it can also be represented with Principles at the bottom. For this discussion, the top-down approach is more useful.

- Principles inform Policies. Those policies may be at the macro (external to the organization) level, in the form of legislation – or they may be at the micro (internal to the organization) level, in the form of internal corporate policies on things. Often the internal principle is triggered by an external principle, and the internal policy may be triggered by an external policy.

- Policies guide the definition of and development of procedures. A procedure, in this context, is a collection of processes and controls that are implemented to give effect to the policy and to the principle.

- Processes are the specific steps and actions that are taken to do the things that are required under the procedure, that gives effect to the policy, that is informed by the principle.

- Outcomes, be they information outcomes or process outcomes, are the measure of the success or failure of the processes, procedures, policies, and principles in the organization.

- Enforcement needs to occur where the outcome of the process or procedure does not align with the expectation or requirement of the policy or the principle.

The role of Governance in all of this is to ensure that Enforcement happens. But, more than that, it is to ensure that the enforcement happens at the right level and in the right way. For example, if the outcome of a process to extract marketing leads from a CRM system to email customer results in customers who had chosen not to receive electronic marketing receiving unsolicited emails, the role of Data Governance is to ensure that there is appropriate accountability for the outcome.

That doesn’t mean beating up on the analyst in Marketing who generated the leads list. That means making sure that there are processes, procedures, policies, and principles in place in the organization that ensure each person in the life cycle of that email marketing information is aware of their role and their obligations to the internal and external stakeholders to that process. It means ensuring that, if there is a breakdown in a process that feeds into the electronic marketing process, that you have controls in place to detect that and act on it to prevent the unwanted outcome. And, where someone in the organization consciously acts in a manner that is not compatible with the processes, procedures, policies, and principles of the organization that they can be held accountable.

This is a key shift in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, which is a broad and principles based piece of legislation. Article 5(2) introduces the “Accountability Principle”. Much like Kennedy’s promise that it was the United States’ objective to land a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s and to return him safely to the earth again, the GDPR requires organizations to be compliant with the core principles of the Regulation, and to be able to demonstrate compliance.

This is only possible with an effective Data Governance framework that links Principles to Outcomes and uses Enforcement wisely, as a tool to correct errant behaviour and ensure the system operates as expected.

Which brings me to my final point on Principles.

Tuesday was a busy day for me. I was scheduled to be teaching a public course on the GDPR with a partner. I was asked late last week to prepare for and attend this Joint Committee of Parliament. There was no fee for doing so.

However, as an Information Management Professional, I feel ethically and morally obliged to lend my insights and experience to important discussions and debates, particularly on matters that have a potentially significant impact on society. Therefore, it was not only an honor to be asked to give testimony, it was something that I simply needed to do. Filthy commerce be damned!

Indeed, as a DAMA International Member and CDMP holder, it’s in the Code of Ethics I sign that I have an obligation to “actively promote the ideals and mission of DAMA International.” Part of that mission is raising awareness of information and data management best practices.

As information and data management professionals, we should work to help implement good data management principles, policies, and procedures whenever we can.