Democracy is a system of government based on certain requirements, two of them being fundamental:free and fair elections,

– alternative sets of policies

– espoused by different political options, which demand multiple sources of information.

The open data initiatives that mushroomed in the late 2000s were expected to foster democratic rule in new and more established democracies.

The premise was simple: the more data released to the public, the more sophisticated and capable the electorate would be to hold elected officials accountable.

Fast forward ten years and the truth is that this expectation has not been fully met, technological advances notwithstanding. As it turns out, the massive release of data into the public domain in recent times neither prevented the current crisis of democracy around the world, nor increased voter participation in flagship democracies of the West.

Why did this happen?

There are two unforeseen factors that contributed to this outcome:

- the politicized use of government data,

- the strengthening of partisanship in the face of hard evidence.

Let’s take a closer look at each of them.

Open Data, Closed View

Politicized use of open data refers to its biased interpretation, i.e. downplaying or overplaying the implications of the data. One current example comes from Brazil, where an ongoing criminal investigation labeled Operação Lava Jato instructed by Judge Sérgio Moro put former President Luiz Inácio (“Lula”) da Silva behind bars. The allegations against Lula revolved around publicly released data that suggested he received an apartment in exchange for government contracts. Lula has denied all the charges, arguing they are simply part of a conspiracy to prevent him to run in the presidential elections. At first glance, his imprisonment would be a testament to how open data initiatives can bring down powerful politicians. On closer inspection, though, there is reason to believe that the Brazilian system of justice and the institutions to improve accountability were manipulated and mismanaged. Judge Moro, who always called himself “apolitical,” recently accepted the invitation of newly elected President Jair Bolsonaro to become his Minster of Justice and Public Security. The conflict of interest was apparent to Gleisi Hoffman, president of Lula’s Workers’ Party (PT), who tweeted: “[Moro] helped elect Bolsonaro, now he’ll help him govern.”

Open Data and Partisanship

The second unforeseen consequence of open data initiatives is that they demonstrate the strength of party identification and partisanship in the face of data-based evidence. Contrary to the expectations of open data enthusiasts, voters in many parts of the world are happy to embrace “alternative facts” if they support their views and values. Intuitively, politicians that depart from evidence-based facts should carved themselves smaller niches and eventually become marginalized; however, the opposite is occurring. Despite the incredible amount of data released by government agencies, post-truth leaders are thriving. A psychologist explains this by making reference to the Dunning-Kruger effect: a cognitive bias in which we asses our cognition skills as more sophisticated than they actually are. As he puts it: “the key to the Dunning-Kruger Effect is not that unknowledgeable voters are uninformed; it is that they are often misinformed— their heads filled with false data, facts and theories that can lead to misguided conclusions held with tenacious confidence and extreme partisanship.”

Driving Forward with Data as Fuel

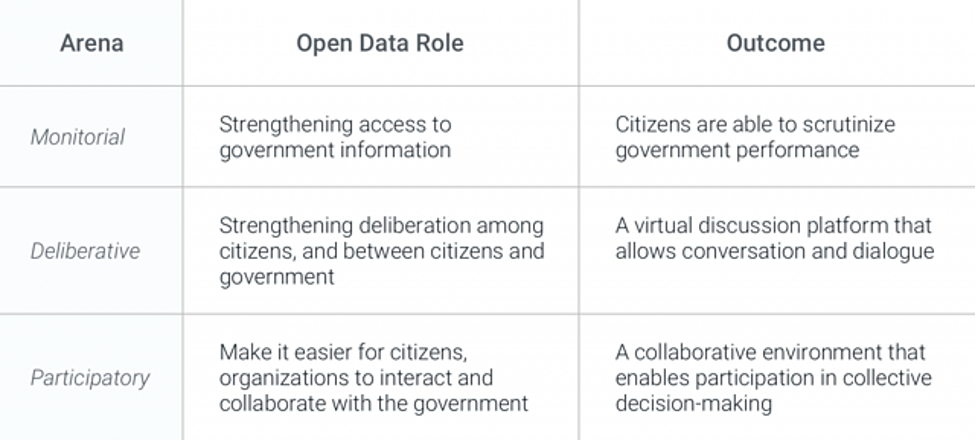

These two unforeseen outcomes do not mean that open data initiatives are misguided or irrelevant for democracy. They do, however, point to one irrevocable fact: publicly available data can be used to serve different, and sometimes opposing, objectives and agendas. For app developers working in tandem with political actors, this means that they need to stop treating open data like a classic “deus ex machina” solution capable of buttressing democracy by its mere presence. In a widely-cited article, Rujier et al. suggest instead that “democratic processes are multifaceted and open data can be used for various purposes, with diverging roles, rules and tools by citizens and public administrators.” These scholars send a warning to app developers that without a deeper understanding of democracy, they are doomed to devise “overly simplistic approaches to open data platform design.” To avoid this, they propose the segmentation of the democratic process into three distinct arenas in which open data plays different roles: monitorial, deliberative, and participatory, for which they propose a particular plan of action as shown here:

Some efforts are underway in the direction set by Rujier et al., particularly with respect to political participation. Take, for example, the app called Represent.me, which aims to increase participation of younger people in the political process. In an interview with The Guardian, its creator, Ed Dowding, argues that open data can aid democracy by creating “new ways to engage more people, build[ing] more consensus, and deliver[ing] more positive action with less bureaucracy.”

“If the public uses the app to share their views on fracking, or new housing, local authorities can use the app to save on consultation fees and more efficiently allocate resources

… [w]e’re not suggesting a revolution – we’re working in parallel with government to help the existing structures work more effectively.”

Ed Dowding

The importance of Dowding’s insight is that the contribution of open data to democracy depends largely on preexisting socioeconomic structures and the way actors compete electorally. From this perspective, the contribution of open data will vary from case to case and change over time, and as a result, there will be instances and periods where it will seem gradual and even modest. Still, it will be pivotal for the future of democracy across the globe.