Signals are converging and leading me to believe that 2025 is the Year of the Knowledge Graph. But before we get carried away with this prognosis, let’s review some of the previous Year of the Knowledge Graph candidates and see why they didn’t work out.

2001

The first candidate for the Year of the Knowledge Graph was 2001. That’s when Tim Berners-Lee, James Hendler, and Ora Lassila unveiled the concept of the Semantic Web in Scientific American.1 Of course, the term “Knowledge Graph” wouldn’t come into widespread use for over a decade — but they were talking about the same technology and the exact same standards.

What made it special was that it was only 10 years earlier that Tim Berners-Lee had unleashed the notion of the World Wide Web. And it seemed like lightning was going to strike twice. It didn’t. Not much happened publicly for the next decade. Many companies were toiling in stealth, but there were no real breakthroughs.

2010

Another breakthrough year was 2010, with the launch of DBPedia as the hub of the Linked Open Data movement. DBPedia came out of the Free University of Berlin, where they discovered that the info boxes in Wikipedia could be scraped and turned into triples with very little extra work. By this point, the infrastructure had caught up to the dream a bit, and there were several commercial triple stores, including Virtuoso, which hosted DBPedia.

The Linked Open Data movement grew to thousands of RDF-linked datasets, many of them publicly available. But still, it failed to reach escape velocity.

It was around June of 2009 when Siri was unveiled at the Semantic Technology Conference created by Semantic Arts. This was about a year before Apple acquired Siri, which was the RDF-based spin-off from SRI International and morphed it into their digital assistant of the same name.

2012

Another good candidate is 2012, which marked the launch of the “Google Knowledge Graph.” Google purchased a Linked Open Data reseller called MetaWeb and morphed it into what they called the Google Knowledge Graph — inventing and cementing the name at the same time. Starting in 2012, Google began the shift from providing pages on the web where you could find answers to your questions, to directly answering them from their graph.

Microsoft followed suit almost immediately, picking up a Metaweb competitor, Powerset, and using it as the underpinning of Bing.

By the late 2010s, most of the digital native firms were graph based. Facebook is a graph, and in the early days, it had an API where you could download RDF. Cambridge Analytics abused that feature, and it got shut down, but Facebook remains fundamentally a graph. LinkedIn adopted an RDF graph and morphed it to their own specific needs (two hop and three hop optimizations) in what they call “Liquid.” AirBnB relaunched in 2019 on the back of a knowledge graph to become an end-to-end travel platform. Netflix calls their knowledge graph StudioEdge.

One would think that with Google’s publicity, the fact that they were managing hundreds of billions of triples, and with virtually all the digital natives on board, the enterprises would soon follow suit. But they didn’t. A few did to be sure, but most did not.

2025

I’ve been around long enough to know that it’s easy to get worked up almost every year thinking that this might be the big year, but there are a lot of dominoes lining up to suggest that we might finally be arriving.

It was tempting to think that enterprises might follow the FAANG’s lead (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google) as they have done with some other technologies, but in the case of knowledge graphs, they have not. That being said, some of the intermediaries that influence enterprises directly now seem to be on the bandwagon. Let’s go through a few.

Service Now

A few years ago, ServiceNow rebranded their annual event as “Knowledge 202x2.” This year, they acquired Moveworks and data.world (major players in AI and knowledge graph, respectively). Gaurav Rewari, a senior vice president at ServiceNow, said at the time: “As I like to say, this path to agentic ‘AI heaven’ goes through some form of data hell, and that’s the grim reality.”

SAP

As SAP correctly pointed out in the October 2024 announcement3 of the SAP Knowledge Graph, “the concept of a knowledge graph is not new…” Earlier versions of HANA (their in-memory database) supported openCypher as their query language; the 2025 version brings RDF and OWL to the forefront, and therefore top of mind for many enterprise customers.

Samsung

Samsung recently acquired the RDF triple store vendor RDFox4. Their new “Now Brief” (a personal assistant which integrates all the apps on your phone via the in-device knowledge graph) is sure to turn some heads. This acquisition has launched Samsung’s Enterprise Knowledge Graph project with the intent of remaking the parent company’s data landscape.

AWS and Amazon

Around 2018, Amazon “acquired/hired” Blazegraph, an open-source RDF graph database and made it the basis of their Neptune AWS graph (offering the option of RDF graph or labeled property graph). Amazon was also working on a grand unification of the two graph types under the banner of “OneGraph.”

It was 2025 when Amazon really made news with the internal adoption of the knowledge graph. Every movement of every package that Amazon (the e-commerce side) ships is tracked in the Amazon Inventory Graph, which is now over one trillion triples, and outperforms the predecessor system by an order of magnitude.

graphRAG

Last year, everyone was into “prompt engineering” (no, software developers did not become any more punctual. It was a job for a few months to learn how to set up the right prompts for LLMs). Prompt engineering gave way to RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation), which essentially extended prompting to include additional data that could be used to supplement an LLM’s response.

A year in, and RAG was still not very good at inhibiting LLMs’ hallucinatory inclinations. Enter graphRAG. The underlying limitation of RAG is that most of the data that could be queried to supplement a prompt, in the enterprise, is ambiguous. There are just too many sources, too many conflicting versions of the truth. Faced with ambiguity, LLMs hallucinate.

GraphRAG starts from the assumption that there is a grounded set of truth that has been harmonized and curated in the enterprise knowledge graph. If this exists, it is the perfect place to supply vetted information to the LLM. If the enterprise knowledge graph doesn’t exist, this is an excellent reason to create one.

CIO Magazine

CIO.com magazine proclaims that knowledge graphs are the missing link in enterprise AI.5 The article, titled “Knowledge graphs: the missing link in enterprise AI,” kicks off with: “To gain competitive advantage from gen AI, enterprises need to be able to add their own expertise to off-the-shelf systems. Yet, standard enterprise data stores aren’t a good fit to train large language models.”

CIO Magazine has a wide following and is likely to influence many decision makers.

Gartner

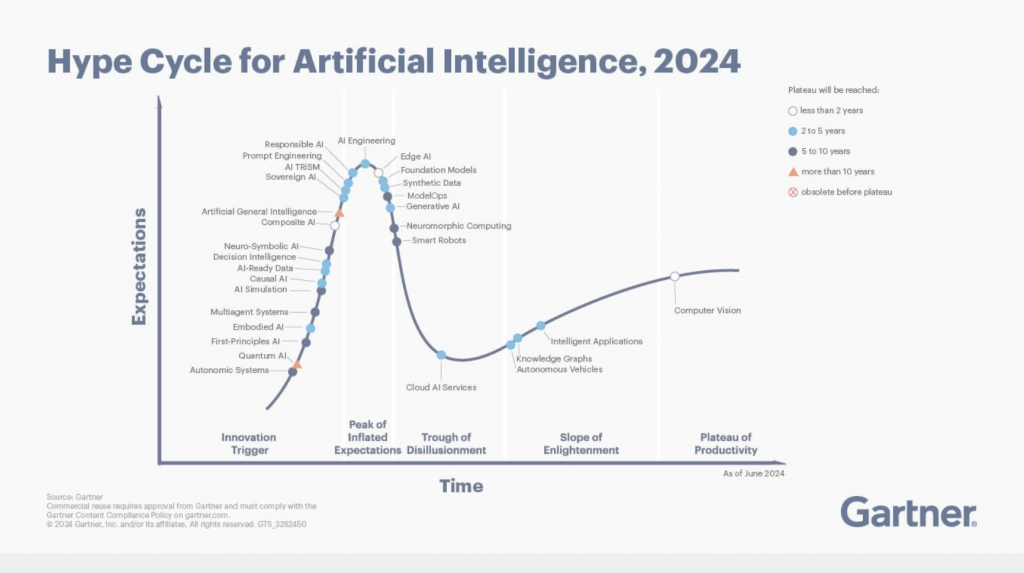

Gartner has nudged knowledge graph into the “Slope of Enlightenment.”6

Summary

Those of you who know me know I’m mostly an anti-hype kind of guy. We, at Semantic Arts, don’t benefit from hype, as many software firms do. Indeed, hype generally attracts lower-quality competitors and generates noise. These are generally more trouble than they are worth.

But sometimes the evidence is too great. The influencers are in their blocks and the race is about to begin. And if I were a betting man, I’d say this is going to be the year that a lot of enterprises wake up and say, “We’ve got to have an enterprise knowledge graph (whatever that means).”

1 lassila.org/publications/2001/SciAm.pdf

Ora has provided an outside the paywall pdf of the article.

2 servicenow.com/events/knowledge.html

3 ignitesap.com/sap-knowledge-graph

4 news.samsung.com/global/samsung-electronics-announces-acquisition-of-oxford-semantic-technologies-uk-based-knowledge-graph-startup

5 cio.com/article/3808569/knowledge-graphs-the-missing-link-in-enterprise-ai.html

6 gartner.com/en/articles/hype-cycle-for-artificial-intelligence