Deja Vu All Over Again

Something interesting has been happening to me over the last few months that I’ve not experienced in a while. Smart and experienced CIOs and their data leaders have been asking me for input regarding how to sell the value of a data program.

The question is a clear sign of the economic times where every dollar is being heavily scrutinized. While it’s about as fun as going to the dental hygienist, overall, I think it’s refreshing and healthy to sharpen up our vision, value propositions, and communication skills.

It’s driven me to revisit the age-old topics of business cases, return on investment (ROI), and how we build support for large data programs. The focus of the column this month is to share a framework that I’ve been working on to help leaders think strategically about the approach they take.

Some Things Have Changed and Others Stayed the Same

After doing a refresh by reviewing a vast array of material published by consultants, industry analysts, and executive leaders, a few things have become very clear:

- Writings on the topic of justifying the value of data have been remarkably similar over the past decades. Most of it is riddled with cliches and analogies that are intended to help convey the value of data to the business.

- The analogies and cliches may have provided value a long time ago, but almost all are condescending and talk down to the modern executive. Today, executives understand the hypothetical “promise” of data. What they want are specifics that relate to their business.

- There is still an indirect relationship between the use of data and business impact. It’s hard to quantify. That has always been true and still is. Sorry, but there is no “easy button.”

- What is very different today is the higher expectation and perception that data needs to be used for direct competitive advantage. That was certainly not the case even as recently as 10 years ago when it was still predominantly just a way to look back and report on what happened.

- In some ways, the previous point has raised the bar and made it more difficult to persuade executives who can challenge and test our value propositions better than ever before.

- These same executives also enjoy more autonomy and have the budget to operate their data and analytic teams if their needs are not met.

Why a Framework? What Is It? What Value Can It Provide?

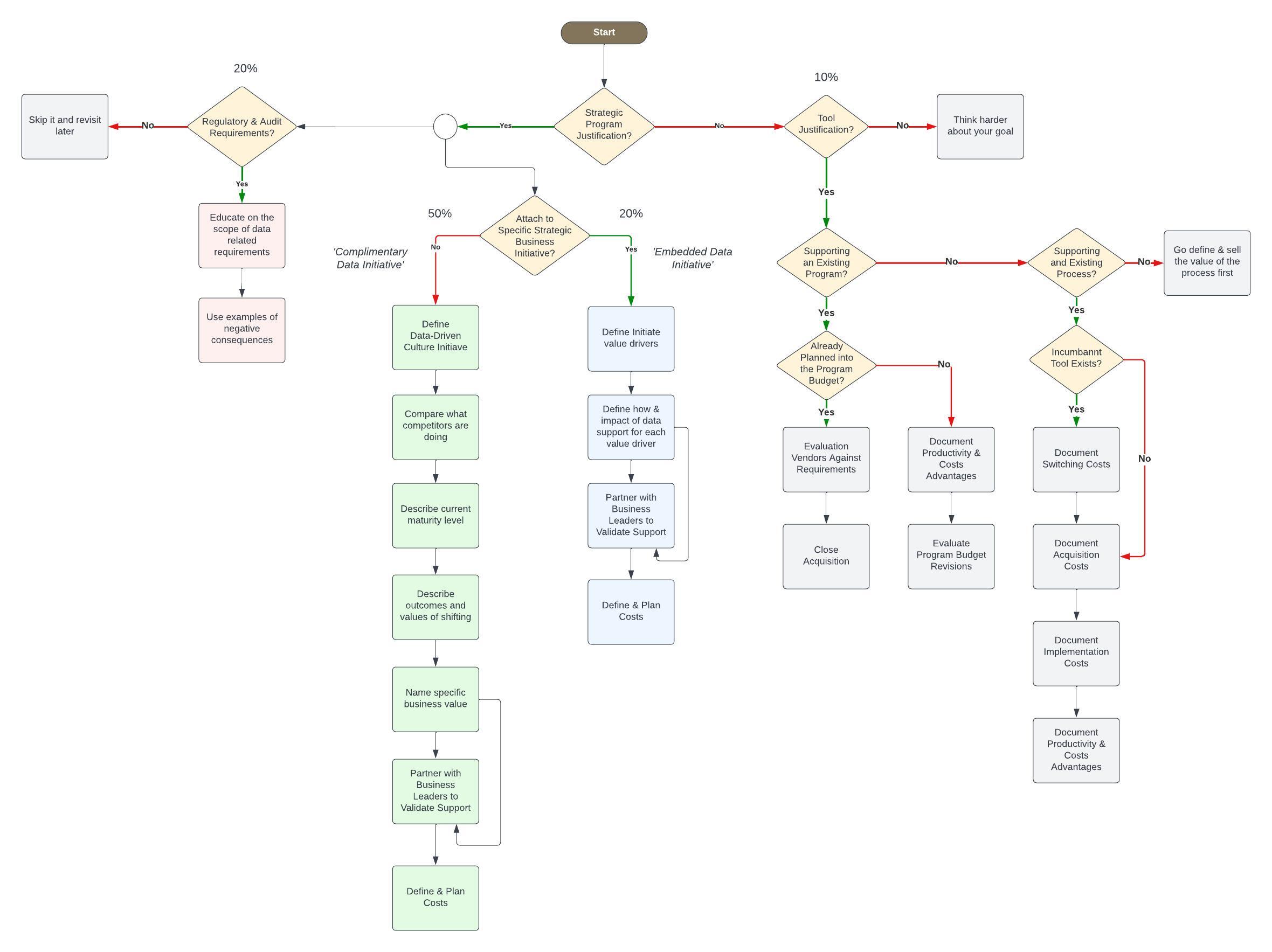

I always default to some sort of model or framework to clarify my thoughts. It also helps me communicate complex material more easily. So, as I’ve been talking to leaders and started to see patterns, I decided to attempt to capture it as a framework.

The framework is the combination of a decision tree and a listing of steps needed to build support and persuade others. It is purposely strategic and not a retread of how to create an ROI model using a spreadsheet. And by strategic, I mean in the sense of helping a leader consider how they want to position their initiative. Even in its nascent, immature state, I’ve been getting positive feedback.

Framework Explanation

This is an abbreviated description of the framework to help you understand what I was aiming for so you can decide if it will be useful for you.

Bird’s-Eye View

As you take in the entire framework you will notice the following things:

- All decision points are yellow triangles.

- From left to right, the pink/salmon color is for governance, green and blue for programs, and grey for tools. I provide more context on these below.

- There are percentages for each major branch. These represent my unscientific, gut feel of the percentage of data leaders I’ve talked to and the path they are pursuing.

- There is one circle symbol heading to governance. This indicates that it’s an “and/or,” meaning someone may do both the governance and the program path or only one.

- The green program branch is labeled “Complimentary Data Program” and the blue branch is labeled “Embedded Data Program.”

First Decision: Strategic Program Justification?

The first decision is pivotal and should not be answered lightly. The essence of it is: Are you trying to establish a strategic data program that will fundamentally change the culture and impact the effectiveness of the entire enterprise? The key is “the enterprise,” not just within the four walls of the CIO’s domain.

If it’s not a strategic program, we can then move to the right and enter a narrower scope of building justification for a tool or platform.

If it is a strategic data program, then we have a rich set of decisions ahead.

Governance Decision: Regulatory & Audit Requirements

The next decision is pretty easy. If you are in a highly regulated industry and/or process personal information, then you have no choice but to have an element of your strategic data program that mitigates corporate risk.

There is very little justification and building of support that has to be done for this. The board’s governance subcommittees and management team are well aware of it because their necks are on the line. The odds are that they will already be demanding this and will welcome the incorporation of data policies and controls into the enterprise risk management framework.

If for some reason, there is a lack of awareness and that is not the case, it usually does not take much education and persuasion related to risk exposure to build support very quickly.

Decision: Attach to Strategic Business Initiatives?

The more difficult decision is whether the strategic data program will be sold as an independent program that is complimentary to strategic business initiates or will be embedded into each strategic business initiative. I realize that that is a bit abstract, so let’s explore it in a more concrete way.

Complimentary Data Program

A complimentary data program would be recognized as a business initiative with its own strategic importance to the corporation. Think of some common strategic business initiatives such as:

- Digital transformation

- Global expansion

- Supply chain optimization

- Environmental, social, and governance (ESG)

Examples of strategic data programs that may be added to that list (not subordinated) could include data literacy, data-driven culture, data marketplace, etc. In this scenario, they would receive the same support and scrutiny as all of the rest.

By carefully studying the steps for this branch, you will notice they are related to education, competitive analysis, maturity assessments, and enterprise value and outcomes. These don’t exist under the embedded data program branch because it’s harder to justify a new strategic program than to fit into something that is already recognized.

What both branches have in common is the hard work required to identify the value of specific business functions and to then partner with leaders to get their validation and support.

Embedded Data Program

An embedded data program would be considered a vital component (subordinate) of each strategic business initiative, but it would not necessarily exist outside the utility and interest of those initiatives. For example, data literacy would be used to support the implementation of digital transformation or ESG.

In some ways, it feels like an exercise in splitting hairs, drawing a distinction between a complimentary and embedded data program. But there are some significant differences. First, there is a clear difference in emphasis and priority. The message communicated is that data programs are not as important and therefore do not have fundamental value to the enterprise. Second, it communicates that data is not an asset with value that is equivalent to intellectual property, physical resources, and others that should be put to work directly for the growth, efficiency, and profit of the business.

Most readers of this column will believe, as I do, that data should be elevated and would be disappointed with this position. But sometimes, it’s the right decision. For instance, it might be useful as a first step to demonstrate the impact to skeptical executive staff or boards who are not likely to support elevating a data program to the same level of importance as other business initiatives.

You will notice that there are not as many steps listed for the embedded choice. The reason is that the bar is lowered for establishing justification. The need still exists but belief and support for the business initiative already exists. Attaching a data program as a contributing element will still take work, especially if it lacked consideration in the beginning, but it will certainly be easier.

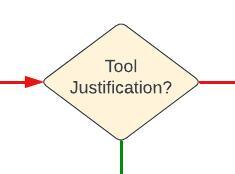

Decision: Tool Justification?

If after careful consideration you decide that you aren’t seeking support for a strategic data program, the path leads to the tool justification branch. The key question is: Are you trying to justify purchasing a tool?

If the answer is yes, then there are more decisions to be made. If the answer is no, then there is a general lack of clarity and confusion.

If you are really in search of a tool, then it must be to either support an existing program or a process like data quality, data engineering, or data operations (DataOps).

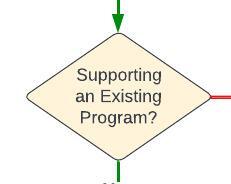

Decision: Supporting an Existing Program?

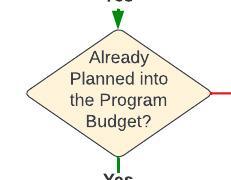

If the tool is intended to support an existing program, then it will logically have already been planned into the program budget or not. If it was, then it’s a pretty easy exercise that does not require much justification. All that needs to be done is evaluate vendors based on known requirements and close a transaction within the allocated budget.

If it was not planned, the hurdle is much higher. A careful case must be constructed to show how the tool that is a “surprise” to program leaders will unequivocally increase productivity or reduce costs in ways that more than offset its cost. In most cases, simply presenting a zero-sum scenario will not be worth the risk and disruption to prior planning. It must have an overwhelming positive budget impact.

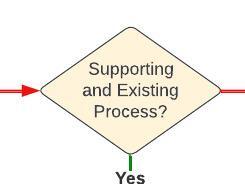

Decision: Supporting an Existing Process?

If the tool is not intended to support an existing program, then it must support an existing process. If it’s not supporting an existing process, then you are at risk of trying to pick a tool before establishing a new process.

For example, picking a data quality platform without understanding data quality requirements, standards, procedures, metrics, or identifying who will be responsible is a bad decision, no matter how convincing the vendor is that their tool covers all scenarios. The recommendation is to stop trying to buy a tool, return to the basics of the process, and identify clear requirements.

If the tool is for an existing process, then it’s replacing an incumbent or a manual effort. In either case, the steps are simply to work through classic tool evaluation, cost analysis, and benefit estimates.

Wrap-Up

It’s fun working with a new generation of data leaders who have high expectations and interest in data being used as a strategic asset for competitive advantage.

Unfortunately, crafting a vision and building executive-level support for data-oriented strategic initiatives has not gotten any easier. I hope you find this framework helpful. I am trying to decide what to do with it next and would love to hear your thoughts and suggestions.