This quarter’s column draws on my keynote for DAMA Calgary’s contribution to DAMA Days Canada last month, which in turn drew on some of the content in the second edition of the “Data Ethics” book I wrote with my colleague Katherine O’Keefe (particularly, Chapter 3 and Chapter 11).

My keynote looked at the thorny question of how we translate the episteme of the various ethics frameworks for data that are floating around into something actionable in the organization — achieving phronesis — the practical doing of things in organizations in a way that delivers information and process outcomes that are considered “ethical,” in the context of society and of the organization as an actor within society.

All very high-browed stuff. But with a simple message: We’re not doing it. As professionals, we need to take a long, hard look at ourselves and think about why that is so. After all, the best way to kill something is to pay lip service to it. Deming was clear. Management needs to “adopt the new philosophy,” which was Deming’s way of saying episteme talks, phronesis walks.

For those readers who are not up to speed on their Aristotelian philosophy, the quick and dirty set of definitions is below, which will hopefully help you follow the thread of this article.

- Episteme: Knowledge, high-level principles.

- Phronesis: Practical wisdom, the ability to put knowledge into practice.

- Techne: Craft, building on a theoretical understanding of principles.

A Model for Thinking about Ethics in Data Management

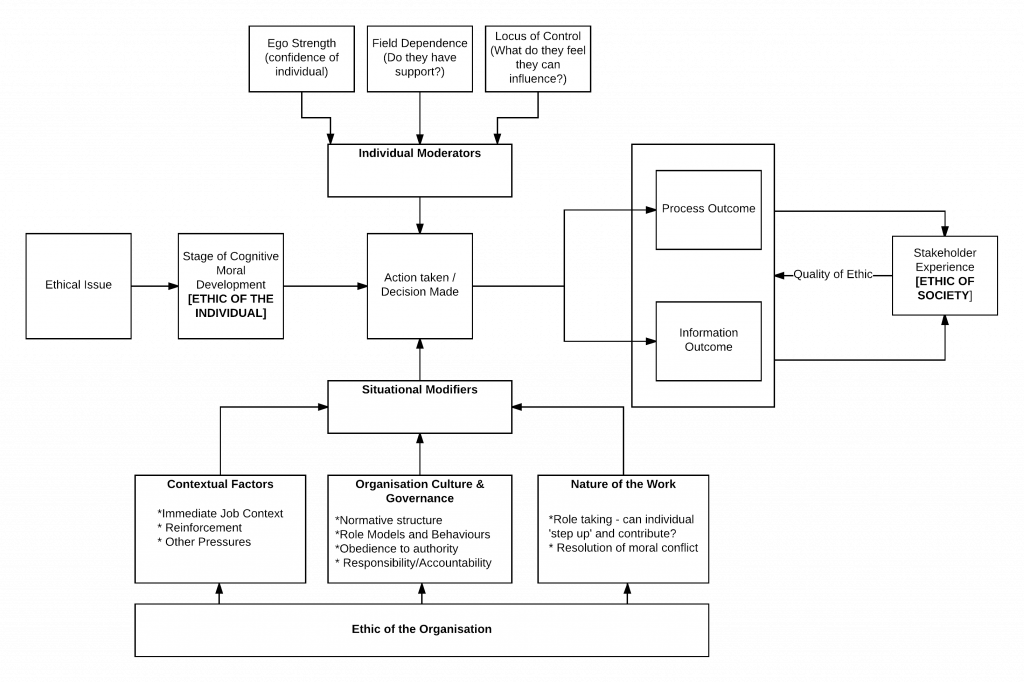

Prior to the writing of the first edition of “Data Ethics” back in 2017, we had developed a framework in Castlebridge that enables a critical examination of the structures that enable or restrict ethical behaviors in relation to data. This model, which builds on existing work in business ethics, has served us well and is repeated in the second edition.

(Click to view larger)

To summarize the framework:

- All data processing results in outcomes, and it is the outcomes of our processing that society determines to be ethical or unethical (for example, the training of an AI model on copyrighted works without compensation to the original authors is a Process Outcome that is generally considered, at best, questionably ethical).

- When people in organizations make decisions or take actions that have an ethical component, they are influenced by their own individual Ethic, by the Ethic of the Organization (as expressed in corporate or team cultures and reinforced by the governance structures in the organization and the formal role of the individual in that structure), and by other factors such as confidence of the individual in themselves, the level of support they have in the organization or from peers, and the practical questions of what they can actually do to exert influence over the decision to be taken. These last items we refer to as “Individual Moderators” of ethical behaviour.

- If the individual feels that something is ethically wrong, in an ideal world, there is a receptive internal forum in the organization where that can be raised as part of governance. Failing that, if the individual has strong feelings on the issue and can muster support to do something, they may be able to influence the Outcomes that are delivered.

Some Data on Ethical Principles and Frameworks

The ultimate expression of the “Ethic of Society” is often considered to be legislation and regulation, but published frameworks on ethics in data management are a useful source of guidance to the “Ethic of Society.” Algorithm Watch has a very useful database tracking global AI ethics frameworks and categorizing them based on whether they represent binding agreements, voluntary commitments, or recommendations.

Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of the 167 frameworks that have been submitted to Algorithm Watch represent “recommendations” and even those that are “binding agreements” lack any substantive teeth. So, these frameworks remain very much at the level of episteme for most data management professionals, not least because the frameworks described by and large lack specific definitions of what the actions are that organizations need to take to put these high principles into practice.

This means that data management professionals (and I would argue that everyone in an organization these days is a data person) find themselves relying on the internal data governance frameworks in their organizations to help them resolve potential ethical issues arising from how data is being put to use and the outcomes that are being delivered. Bluntly: it is rare to find an organization that has matured its governance of data to a level where these conversations are easy to have (even where it is legally required to have them, such as under EU data protection laws, which require consideration of how the processing of data will impact on the rights of individuals).

So, what’s a data geek to do?

The Role of Professional Bodies

Professional bodies come in all shapes and sizes. Since the earliest days of trade guilds back in ancient Mesopotamia and the Collegium of Ancient Rome, guilds have promoted the development of professional standards in the execution of a trade or craft. While the promotion of working conditions and standards is more often associated with the modern trade union movement, historically guilds also had a role in ensuring standard terms for contracts of engagement.

Today, professional bodies like the ACM or DAMA International might be considered a form of “Guild.” The ACM does provide an ethics framework for its members that includes, among other things, positive duties to:

- Maintain high standards of professional competence, conduct, and ethical practice.

- Know and respect existing rules pertaining to professional work (including national and international laws).

- Give comprehensive and thorough evaluations of computer systems and their impacts, including analysis of possible risks.

The DAMA Code of Ethics for members does not contain any equivalently clear statements of minimum standards of professional ethics by DAMA members.

Professional Ethics as a Moderator of Ethical Behavior

Codes of Professional Ethics, particularly where there is a sanction associated with infringing the provisions of such a Code, are valuable Individual Moderators of Ethical Behavior, as they provide the individual facing an ethical question with a degree of peer support and “field dependence.” At a minimum, the person who is raising an ethical concern can present it as a concern arising from a professional ethical obligation to give a comprehensive evaluation of the impacts and risks of a particular computer system.

This is a concept that will be familiar to professions that have established and robust ethics frameworks. Lawyers, for example, can raise concerns about the ethical conduct of other practitioners with regard to how they handle client funds or privileged information. Of course, in these circumstances, the respective “guild” or professional body usually has some form of sanctioning power. And in mature professions, those sanctions are often supported by legal frameworks around whether or not you can carry on that profession if the professional body has disciplined you.

We are not there yet in data management. But, we are at the point where, for members of certain professional bodies in the data space, an individual can at least point to an obligation under the Code of Ethics for their Guild of Data Professionals as the basis for raising a concern or pushing back. However, not all professional bodies in the data space have a defined Code of Ethics for Data Management. For example, the International Association of Privacy Professionals has no Code of Ethics, and the DAMA International Code of Ethics is internally focused on the ethics of DAMA instead of providing a baseline set of behaviors for the ethics of DATA.

A first step in turning the episteme of ethics in data management into something practical and tangible would be for relevant professional bodies to provide their members with some core ethical principles related to the execution of the craft of data management in an ethical manner. Without that, each individual practitioner is on their own, relying on their own knowledge and sense of ethics when addressing complex issues.

Societal Awareness as a Moderator of Ethical Behavior

Related to the question of professional codes of ethics as a tool for translating episteme into phronesis is the importance of raising social and societal awareness of the issues and the practicalities of data management and ethical use of data. In short: rather than preaching to the choir of data people, professional bodies need to step up and begin to act as educators to society.

Data and the various uses we can put it to are not magical. But it can let us do magical things. As Arthur C. Clarke famously put it: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” But, if we look back to the ACM’s Ethics Code, it is arguably one of the jobs of data professionals to explain to people how the magic happens and to explain how the magic can go wrong if we get the inputs wrong or don’t have the right safeguards in place.

In Calgary, I expressed a concern that, as data professionals, we had sleep-walked into a form of “Nanny State,” where the actress Fran Drescher had done more this year to raise awareness of the Process Outcomes and social impacts of emerging data technologies and influence safeguards on the use of such technologies, than anyone in a leadership role in a data management professional body.

But my frustration here echoes the frustration I and others, such as Tom Redman and John Ladley, have felt with how the data management professional community has been communicating for several years. Until we begin to engage outwards with the stakeholders in our craft, we will not see the step change we need in how data is managed as an industry and societal asset. In that context, it will continue to fall to individuals to raise awareness of the ethical issues as well as the quality problems.

It’s time for professional bodies to stop preaching to the choir and to start engaging and educating outside the bubble of our own episteme.

The Virtuous Craft of Data Management

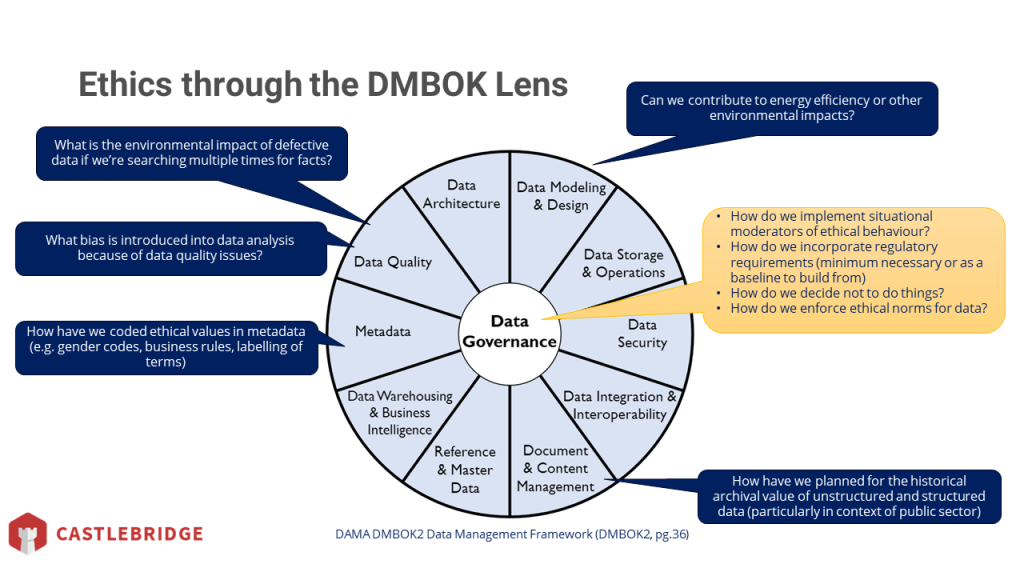

In the book, and in my keynote in Calgary, I refer to episteme and phronesis. However, in my keynote, I took a little time to explore how ethical issues can raise themselves in practice through the lens of the DAMA DMBoK Wheel.

The DMBoK is the description of our Data Management Craft set out by a Guild of Data Management professionals. And I use the term “craft” here for a reason. In the writings of Aristotle, the concept of techne describes the relationship between pure knowledge and principle and the application of that knowledge in the form of a craft — a discipline that brings something into being by the application of wisdom. For example, we might have the theory of what a house is as a concept. But the craft of the architect is to develop designs and blueprints for that house so that the concept can made real.

One of the key ways in which professional bodies can help bridge the gap between the episteme of data ethics and the phronesis of practical actions on a day-to-day basis in our management and use of data is through the development and refinement of the craft of data management. In this context, the DMBoK and the different data management disciplines described in it represent this techne. By promoting awareness of this craft, and by continually improving its relevance to the emergent episteme of the evolving technical and conceptual landscape for data management (remember: episteme is the high concept/theory stuff), professional bodies can provide a framework within which we can start to dig for answers about how we can practically put the episteme of fluffy ethical principles and guidance into practice.

In short: by working the DMBoK and considering how ethical issues can be raised or resolved in the practical execution of specific data management crafts and skills, we can begin to build an ethical operating model and achieve phronesis, the practical doing of things (praxis) to give effect to an ethical principle.

For example, most organizations these days have ESG obligations and there are efforts in place to improve the energy and natural resource consumption of the organization. This is often expressed in an abstract ethical principle.

For a data professional looking at that challenge through the lens of the DMBoK’s crafts, we can reframe the principle in terms of:

- Data Modeling: Can we improve the energy efficiency of data search and retrieval by improving the modeling of the data at different levels (concept, logical, physical)?

- Data Quality: Can we reduce the environmental/energy impact of data scrap and rework by improving data collection and handling processes?

- Metadata Management: Can we reduce the energy consumption for search/retrieval/storage of data in structured/unstructured forms by improving data classification practices?

These are just simple examples. The challenge for data professionals will be to take a craft framework such as the DMBoK and use it as a lens to focus the discussion of high concepts in ethics into actionable things and implementable practices. But this is an essential step that we need to take if we want to turn the episteme into phronesis.

After all, as the social reformer and ethicist Jane Addams wrote: “The only evidence of ethics is action.”

Tying It All Together

Professional bodies have a critical role to play in the development of and implementation of approaches to data management that deliver ethical outcomes. We urgently need to move the discussion beyond the episteme and into phronesis. The techne of professional bodies of knowledge is one lens we can use to focus those discussions into actionable practices.

In Calgary, one of the attendees raised the point that in physical engineering and construction professions, individuals are expected to sign off on their work and on their designs. While today, this is a legal and regulatory obligation in many cases, historically, it has its roots in the master craftsman putting their mark on their work, to show it was done to the standard required by their guild. This simple practice puts a stark focus on ensuring that professionals apply the disciplines of their craft correctly and ethically.

But beyond the development of our craft as professionals, professional bodies have a critical role to play in supporting and enabling individual moderators of ethical behavior through the development of meaningful, actionable, and ideally sanctionable, codes of ethics for data management. This is an area where we are sadly lacking leadership at this time, but it is a critical gap. What am I, as someone who identifies as a data management professional, expected to do when faced with over-hyped claims about a technology or a data management practice? What is my duty to society to educate people about how the data magic happens?

Finally, a thought.

Two trade unions in America, the Screen Writers Guild and the Screen Actors Guild, did battle this summer to address the impact of AI on their professions and on the people working in their craft.

Given the potential for AI and other technologies to impact the nature of the roles and jobs that data management professionals may have now and in the future, the time may come when the talking-shop data professional bodies of today may need to evolve to be representative bodies for our profession or develop alliances with worker representative bodies to ensure that the ethical implications of the impacts of new technologies on new entrants, mid-career data professionals, and venerable data geeks are properly considered as we embrace these tools and reshape our profession.