Part I

When I finished my last column, “Through the Looking Glass: Metaphors, MUNCH, and Large Language Models,” I stated my intention to follow up with part II. I would cover whether a knowledge graph’s vocabulary of “triples” relates to metaphoric thinking. I even considered challenging an LLM on its ability to understand metaphors to the depth of Umberto Eco’s interpretive rules.

But that was three months ago, and I’ve gone off that idea of focusing on LLM’s ability or lack of such to understand metaphors. In the interim, I listened to Evgeny Morozov’s epic podcast “A Sense of Rebellion.”1 He distills a decade of research into 10 marvelous episodes about a little-known secretive lab in the late ’60s on Boston’s Lewis Wharf, run by a group of truly eccentric, brilliant, and excessively flawed intellectuals who dreamt of a very different approach to technology, especially AI, than what was growing at the same time at MIT.

Today we often hear AI translated to “augmented intelligence” when it comes to how AI will “help” people. From IBM: “IBM’s first Principle for Trust and Transparency states that the purpose of AI is to augment human intelligence. Augmented human intelligence means that the use of AI enhances human intelligence, rather than operating independently of, or replacing it.”2 This is the inheritance of the ’60s technology focus on human augmentation. Human augmentation, Morozov explains, focuses on creating a symbiosis between human and computer: The computer taking over the more mundane, repetitive tasks, allowing the human to focus on the high-level tasks. The goal was (and still is) to increase productivity. The flaw (or is it a feature?) is that if the computer’s capabilities expand to the higher-level tasks, the human becomes expendable.

Avery Johnson and Warren Brody are “c’s lead protagonists. They believed in a different approach to technology: “human enhancement.” No, this isn’t about genetic engineering or cyborgs. Rather, it’s the concept that technology can enhance what makes us most human: our curiosity, our playfulness, our capacity to change. This is exactly the opposite, Morozov observes, of the direction much of today’s technology to outsource what makes us human.

I won’t try to give more details here on “A Sense of Rebellion.” I cannot do this incredible podcast (and the collection of texts and pictures Morozov has gathered on the website) justice. Suffice to say that Johnson and Brody’s ideas resonated with me as had Umberto Eco’s writings about metaphors as cognitive instruments. I don’t think it’s particularly interesting to see if ChatGPT can understand metaphors as well as humans. I’d rather speculate about a “human-enhancing” LLM. Could such an AI tool contribute to the cognitive experience of a person interpreting a metaphor?

First, though, I will probe into Eco’s interpretive rules for metaphors, from his book “Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language.” We’ll find that one of the tools he recommends is an ontology. Ontologies are central to knowledge graphs and the semantic web. So, we are not completely ignoring the fact that TDAN is a publication devoted to data!

Part II

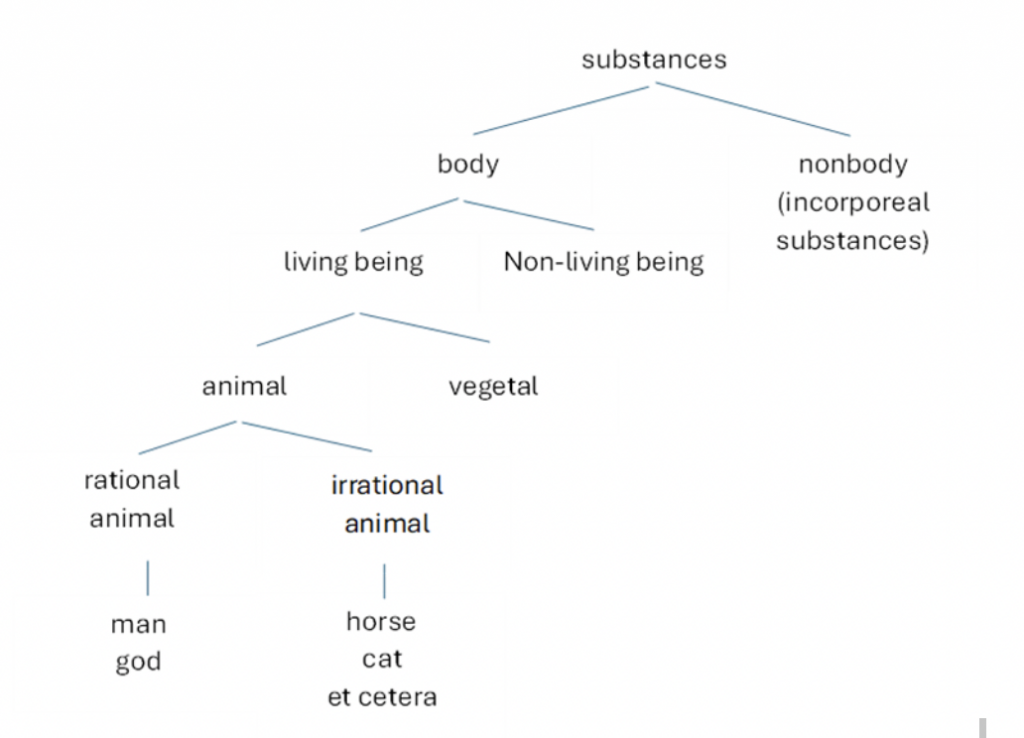

Eco describes five rules for the “co-textual” interpretation of a metaphor. But Eco explains these rules with linguistic terminology far more obscure than “co-textual.” By the way, “co-textual” refers to “the words surrounding a particular word or passage within a text that provide context and help determine meaning.”3 An easier way is to share his analysis of one metaphor. Before I do that, I need to introduce an ancient type of ontology (yes, here’s the tie-in, finally to knowledge graphs and ontologies!). This is the Porphyrian tree, which, per Wikipedia, dates back “to the 3rd-century CE Greek Neoplatonist philosopher and logician Porphyry.”4 It’s a simple, straightforward concept. Each level has just two branches, differentiated by a single trait. One example Eco includes is as follows:5

It’s clear that this ontology is quite limiting. As Eco points out, the “differentia” that separates each branching of the tree is insufficient to distinguish man from a god. You would need to construct a different Porphyrian tree to distinguish between mortal and immortal. Dean Allemang defines an ontology in his course “Knowledge Graph Architecture for the Enterprise” as a “sharable, modular piece of metadata, where modular means self-contained.”6 These Porphyrian trees are definitely not self-contained.

Eco spends part of his chapter on dictionary vs. encyclopedia (a fascinating topic for another time!), documenting the weaknesses of Porphyrian trees recognized by medieval philosophers, from Abelard to Aquinas. He finishes with: “The tree of genera and species, the tree of substances, blows up in a dust of differentia…”7

And yet, Eco makes Porphyrian trees a key part of his approach to interpreting metaphors. We will see how shortly, as we follow one example Eco analyzes.

Eco cites a metaphor which happens to be an Icelandic riddle, “the house of the birds” as the sky. He begins by examining “house” vs “birds”: how they appear, what they are made of, what they do. A house is rectangular, closed, covered, and a bird has wings, feet, etc. A house is inorganic, a bird organic. A house rests on the ground, and a bird flies in the air. Eco refers to these as “interesting differences.” He now suggests the need for a kind of logic called “abduction” (as opposed to “induction” and “deduction”). I had never heard of this definition of abduction, so it requires a brief digression.

The Oxford English Dictionary never lets me down: it explains this meaning of abduction as “Chiefly Philosophy. Originally in the writings of C. S. Peirce (U.S. philosopher and logician, 1839–1914): the formation or adoption of a plausible but unproven explanation for an observed phenomenon; a working hypothesis derived from limited evidence and informed conjecture.”8

C. S. Pierce is Charles S. Pierce, who, among his many accomplishments, was one of the founders of the science of semiotics. I referenced his “tripartite semiotic model” in my article The Unique Identifier of the Rose. Given abduction’s philosophic lineage, I’m not surprised Eco makes it central to interpreting metaphors. The OED includes a wonderful example of abduction, making it much easier to interpret:

“If we enter a room containing a number of bags of beans and a table upon which there is a handful of white beans, and if, after some searching, we open a bag which contains white beans, we may infer as a probability, or fair guess, that the handful was taken from this bag. This sort of inference is called making a hypothesis or abduction.”

J. K. Feibleman, “Introduction to Peirce’s Philosophy,” iii. 122

You could say that making an abduction is equivalent to making an educated guess.

Let’s get back to the riddle “the house of the birds.” Eco now compares the characteristics of the “house” mentioned above with those of “sky.” Formless and open, natural, made of air, and not a shelter. Again, all the characteristics, the components, of “house” and “sky” are in opposition. If one builds a Porphyrian tree based on the opposition of the essences of house (Earth) and sky (Air), you will find they join a node with the property “Element.”

So, what now? Eco suggests the interpreter draws interferences from related “semes” (units of meaning). “What is the territory of men and what is the territory of birds? Men live in closed (or enclosed) territories, and birds in open territories. New Porphyrian trees are tried out: closed dwelling or territory vs. open dwelling or territory… If a man is menaced, what does he do? He takes refuge in his house. If a bird is menaced, it takes refuge in the skies. Therefore, enclosed refuge vs. open refuge. But then the skies that seemed like a place of danger (producing wind, rain, storm) for some beings become a place of refuge for others.”9

Eco suggests this process of inference and abduction, finding surprising similarities and interesting differences, can go on and on, leading to “unlimited semiosis.” This is what makes a metaphor “‘good’ or ‘poetic’ or ‘difficult’ or ‘open.’ It allows “inspections that are diverse, complementary, and contradictory.”

This is the metaphor functioning as a cognitive instrument to the highest degree. As we stretch our minds to interpret, to abduct, to draw on our personal and cultural history, there is a “process of learning,” as Aristotle realized. This makes it much more interesting to consider the value of humans interpreting metaphors than machines.

Part III

Evgeny Morozov makes an intriguing statement about generative AI in a recent article for Boston Review, Can AI Break Out of Panglossian Neoliberalism?

“In particular, generative intelligence — whether artificial, human, or hybrid — can transcend mere extrapolation from past trends. Instead of perpetually acting as stochastic parrots, these systems have the potential to become stochastic peacocks, embracing diversity and novelty as their core values. This shift can foster new perspectives and outlooks on the world, advancing beyond the confines of predictability and stability.”

For those who haven’t heard the term “stochastic parrot,” Dr. Emily Bender coined it in a paper she wrote with Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Margaret Mitchell (using the pseudonym Shmargret Shmitchell) in 2021, “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” The paper defines it this way: “Contrary to how it may seem when we observe its output, an LM [Language Model] is a system for haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms it has observed in its vast training data, according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any reference to meaning: a stochastic parrot.”

The idea that LLMs, as stochastic parrots, actually understand metaphors is nonsensical. The papers I reviewed in my last column assessed how LLMs appear to interpret some metaphors. This is nothing but their statistical models generating reasonable-sounding text responses, based on the training data the models have ingested. I had planned to test ChatGPT 4o’s ability to follow Eco’s methodology for metaphor interpretation. I could have carefully engineered prompts, but I’d succeed at nothing more than prompting the LLM to do a parlor trick.

What is Morozov suggesting about Generative AI systems becoming “stochastic peacocks”? Earlier in the article, Morozov summarizes Warren Brody’s and Avery Johnson’s humanistic bias towards technology (elaborated in full in “A Sense of Rebellion”). They believed it “could cultivate more discerning, sophisticated, and skilled individuals who strive for novelty.” Morozov takes their idea of a smart chair, as an illustration. This is not the smart chair sold to us today. These seek to provide the perfect configuration based on tons of training data, or from constant surveillance of its owner. Morozov’s “subversive smart chair” behaves differently (italics are mine):

“Suppose one cushion combination forces the user into a yoga-like position they had never tried before — and they like it. They register their feelings via the controller’s interface. This, in turn, results in an even more exotic set-up that challenges them further. The controller doesn’t need to understand “novelty” or evaluate it; the user handles this interpretative work. As a result, the controller can start with a random combination of shapes and, through user interaction, arrive at a completely novel configuration.”

Today’s LLMs calculate the next word we want to see or hear about a metaphor. As Dr. Bender might say, the models “extrude text” which may be close to a person’s interpretation. But a “responsive” LLM might answer a person’s question about a metaphor’s meaning differently. It generates a random Porphyrian tree based on aspects of the metaphor’s words. The tool might then ask the person for an abduction based on interesting differences or startling similarities. The person would respond with an interpretation. This might trigger generations of more Porphyrian trees. The LLM might extend the metaphor’s possible interpretations across cultures and geographies. At no time would the tool issue the “correct answer.” Instead, the person could explore this metaphor for however long they liked. The tool would always leave the door open for more, for Eco’s “endless semiosis.” The human enhances their knowledge, abduction, and interpretative skills. The person becomes open to a broader range of perspectives.

I think this is one example of Morozov’s “stochastic peacock.” An array of colors presented to the human based on the person’s responses… but meant to surprise, challenge, stimulate. I am sure AI engineers will tell me I could get this today with the right prompts, or better training data, but I’d be doing nothing but teaching a stochastic parrot new tricks. Sorry, not interested. I, like Morozov, find Brody and Johnson’s vision much more interesting… and hopeful…

Reference

1 A Sense of Rebellion (sense-of-rebellion.com)

2 ibm.com/blog/best-practices-for-augmenting-human-intelligence-with-ai/

3 slideshare.net/slideshow/what-is-co-text/88098083

4 wikipedia.org/wiki/Porphyrian_tree

5 Eco, Umberto, Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language, 1984, First Midland Book edition 1986, pg.60.

6 Allemang, Dean, ©2021 by eLearningCurve LLC. All rights reserved. I recently completed this excellent course and recommend it highly.

7 Eco, Ibid, pg. 68.

8 “Abduction, N., Sense 3.b.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, September 2023, doi.org/10.1093/OED/1132479765.

9 Eco, Ibid. pg. 120