Yes, let’s talk about data governance, that thing we love to hate. I just attended the 17th Annual Chief Data Officer and Information Quality Symposium in July, and there, I heard many creative suggestions for renaming data governance. Calling it data enablement, data trust, data utilization, and many other names to try and avoid the resistance some people seem to have to the idea of being governed. Some suggested just calling it data quality (one of my favorite ideas!) while others suggested we should not even name it but having it be the unnamed understanding of how we go about managing data in the organization.

Personally, I do not have any objections to any of these naming approaches if it works for your organization. However, regardless of the name or lack thereof, I do believe that every organization must have some framework in place that defines every employee’s role and responsibilities for data to achieve coherence in your data operations. Coherence simply means that whenever there is a directive involving data, the recipients understand what it means. They know what should be done, and who should do it. In other words, it makes sense, i.e., the message is not incoherent, it is meaningful and actionable. While having data governance, and perhaps to some extent data literacy, is necessary to achieve data coherence, it is not sufficient. To achieve data coherence, data governance must be understood in a broader context within the organization.

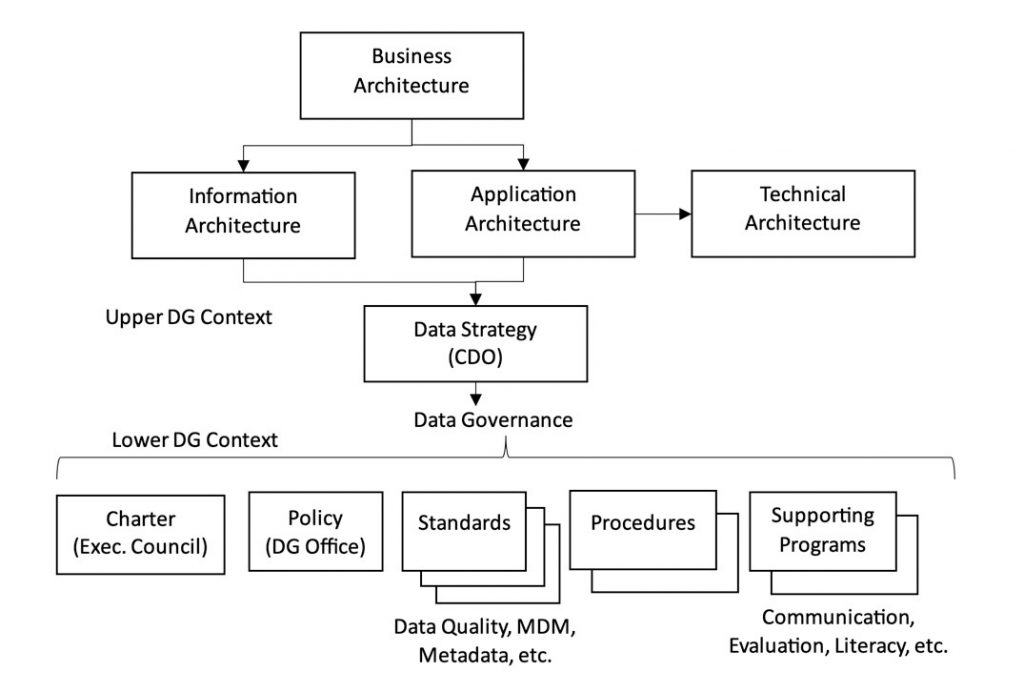

To understand this context, let’s back up and consider the bigger picture starting with enterprise architecture. While there are many different frameworks for enterprise architecture, they all have certain essential components. They all define a business architecture component that explains why the enterprise exists. Business architecture answers the question, what is the enterprise trying to accomplish? What is its mission and its objectives? Business architecture then forms the foundation for the information architecture component. Information architecture defines the information needed to accomplish the mission and objectives set out in business architecture. In turn, the application architecture component defines how the information should be transformed, integrated, and applied to meet the mission and objectives. Finally, there is a technical architecture component that defines how both the information and application architectures will be implemented.

We all know how easy it is to be caught up in the details of daily operations and lose sight of the big picture. But the importance of going back to the basics and aligning ourselves with the mission and objectives of the business is fundamental to the success of every program in the organization. This not only includes the data governance program, but also programs such as data quality, master data management, and data literacy. Too often we tend to jump right to details without taking time to understand how, or if, what we are doing moves the needle in achieving the organizations KPIs.

But for data governance to be effective, there is one more piece that must be in place that is often overlooked. That is the need to develop a robust data strategy. The development of the data strategy should be led by the Chief Data Officer (CDO). The data strategy transforms the information architecture and application architecture ideas into an executable plan. While an important component of a data strategy is to define and implement a data governance framework, the strategy addresses broader issues such as, does the organization need to obtain third party information, and if so, where will it come from, will operations move to the cloud, remain on premise, or be hybrid, will some data operations be outsourced, and if so, to whom, will there be data products, data managers, data fabric, and so on. The answers to these questions will provide the context needed to establish an effective data governance program. The business architecture, information architecture, and the data strategy can be thought of as the upper context of data governance.

Then there is the structure of the data governance program itself starting with a charter. The data governance charter gives birth to the program and gives it authority. The charter should be approved by the executive team. It should also define the data governance structure. The charter will establish the roles and organizational structure of the program such as its leadership, what committees or boards it will have, who will be on them, how and what decisions they will make, will there be business and technical data stewards, how will they be organized, and much more.

Another key artifact of a data governance program is a data governance policy that sets out the scope and goals for the program. Will the program oversee all data or only certain domains or business units, will it include data analytics, will encompass master data management, data models, data quality, and address regulatory compliance. Typically, the policy is very aspirational and sets out goals, but not requirements. Most of the details in terms of requirements and responsibilities for each area addressed by the policy can be defined in individual data governance standards. Each standard is linked to a specific goal of the policy such as achieving data quality. Each standard defines its scope and specific requirements for what must be done. For each requirement, the standard should define who has responsibility and accountability for meeting the requirement. It is through the standards that coherence in data operations is obtained. From the standards, each employee should be able to understand exactly what they are responsible and accountable for with respect to data.

One advantage in having separate data governance standards is that it gives the organization flexibility to update and modify existing standards and add new standards as needed without the need to amend and approve the entire policy. It also allows the data governance program to grow incrementally. While the policy may entail many lofty goals, these can be addressed in smaller steps through the standards, embracing the think big, start small, move fast philosophy.

In addition to the charter, policy, and standards, there can be other components such as a communication plan for the program’s internal and external stakeholders, an evaluation plan for the program, and for certain critical data processes there may be data governance procedures defining in detail how each step of the process will be carried out.

The charter, policy, standards, procedures, along with other plans such as communication and evaluation can be thought of as the lower context of data governance. Putting all of this into a diagram looks like this.

If you are thinking about the structure of your data governance (or enablement or trust) program, I hope this discussion has been helpful. Everyone will have their own version, but most of the components should be there in one form or another, but don’t leave out the data strategy!